Dutch the store

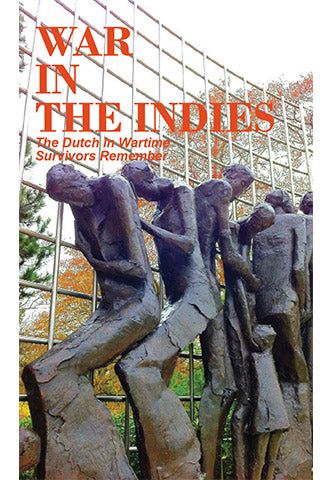

War in the Indies

Couldn't load pickup availability

The Dutch in Wartime: Survivors Remember is a series of books with wartime memories of Dutch immigrants to North America, who survived the Nazi occupation of The Netherlands.

Book 6, War in the Indies, covers the occupation of the Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia) by the Japanese and the wholesale incarceration of civilians of European and partial European descent in internment camps, where a cruel regime caused immense suffering and a high mortality rate.

Designed and written to be easily accessible to readers of all ages and backgrounds, these books contain important stories about the devastating effects of war and occupation on a civilian population.

Edited by Anne van Arragon Hutten.

96 pages

Historical background, 2 maps and 14 wartime memories.

ISBN: 978-0-3968308-7-7

On the cover: ‘Monument for the Indies’, by Jaroslawa Dankowa, erected to remember the civilians and soldiers who suffered in the Dutch East Indies during World War II. (Photo: Sanne Terpstra)

READ AN EXCERPT

I was born in 1934 in Yogyakarta on the island of Java of Dutch parents, the oldest of three children. While I grew up we had a nice home, my father had a beautiful car, and I had everything I could wish for.

Not long after the war began in 1942, Japanese airplanes flew overhead and bombed our airport, while Japanese soldiers marched into our city. My sister and I thought it was so funny to see these short, stout soldiers strut pompously down the main street, with their sabers that were much too long for them clicking on the pavement. The next day they closed our school and made it into a prison where they interned many men, including my father. That was the end of school for us.

(…)

Not long after this we were told to leave our home, taking only our essential belongings. Our beds would be shipped separately; everything else was to be left behind. My mother, my sister and brother and I got ready and went to the train station where a very frightening scene awaited us. Soldiers with guns and bayonets were stationed about twelve meters apart alongside the train. As we boarded, our Indonesian servants cried and tried to help us, but were roughly pushed away. We children carried backpacks containing things we needed, with favourite toys tied to the straps. Right there, watching my anxious mother and the crying children, I made up my mind that my childhood was over, and that from now on I had to be strong for my mother. I was eight years old and after this I could never be a child again.

In the train on the way to the prison camp the Dutch women started singing. I could never get over their sense of humour. This was one thing the Japanese failed to understand, and many times this singing was what carried us through.

Arriving in Banjoe Biroe, the filthiest prison one could imagine, we were assigned our places. The Japanese camp commander appointed Dutch leaders who would report to him and be responsible for organization and carrying out orders for the various blocks and spaces. Our family was fortunate to get a separate room for the four of us. The first thing the Dutch women did was to scrub the facilities.

The beginning of our internment was not too bad. There were about 2000 of us in this camp. We received food every day, although it was only just enough.

(…)

More and more people from other camps were crammed into ours. The beds were removed, we lost our room, and instead of beds, wooden platforms were built. Every person was assigned 50 centimeters to sleep on. At night children cried, others coughed, some people fought, and there was not a moment’s peace. Restful sleep was impossible.

There were three rows of plank beds (britsen) along the three walls of the ward. The door to the wards had been removed. Sometimes the Japanese guards would come in the middle of the night and shine their flashlights right into our faces. Many years later my mother would still wake up screaming because she had nightmares about this. Sometimes the water was shut off for a whole day and there was nothing to drink. Other days we were told the water was poisoned, so we did not dare drink any and that in a hot, tropical country! Every morning we had to stand at attention in rows of five. The person in front had to count in Japanese. We children always volunteered as we thought it was fun to learn Japanese, and we did it with great enthusiasm. After the counting there were three commands: Yutskay! (stand at attention), Keray! (bow exactly ninety degrees), and Moray! (stand up straight).

With the lack of healthy food and cleaning supplies, disease became rampant. My mother became sick with dysentery and then beriberi. Many people had swollen feet and legs because of the hunger. In the end it also affected the mind, and all people could talk about was food. We were graciously allowed to collect and cook Agatha snails. With some imagination they tasted like chicken. We older girls were allowed to go outside the camp under the guard of a Japanese soldier and collect ketella (cassava) leaves. After boiling these for three days they tasted a bit like spinach. Sometimes I wandered away and saw a bunch of bananas or other fruit and would hide them in the center of my knapsack. I would put lots of ketella leaves around them. This was strictly forbidden, but I did anything I could to keep my mother alive.

Very early in the morning I would go down what we called ‘Canary Lane’ to feel the ground to see if I could find any canaries, as we called the big nuts that fell from the canary trees. They were very nourishing. If you went there too late, they would be gone, as other people also picked them up. On one such expedition I wandered away from the guard and came upon an old cemetery where skulls and other human bones were lying right on the ground. As they were not buried very deep, it seemed they had worked themselves up out of the ground. In the centre of this field of death grew beautiful lilies. I stood there for a while, and somehow this gave me great peace.

Our life continued, with hunger, hard work, carrying heavy pieces of wood to the kitchen, picking grass, intimidation, and always the yelling of the Japanese. We could never do anything right. Any time of day, as soon as any Japanese appeared, we were supposed to do the bow routine. If it was not exactly a ninety-degree bow, a beating would follow. On one such occasion two very old ladies were beaten with iron rods. It was hard to watch those scenes.

(…)

At Christmas 1944, we found a little imitation Christmas tree and some candle stumps. We lit our candles and the little tree promptly caught fire. So much for our little Christmas.

Most of us did not think we could last much longer, but we started singing, ‘Oh come, all ye faithful’. To our amazement we heard men’s voices far away answer us with the next verse. This really encouraged us. Many years later at a market in Amsterdam, we met a man who had been in that men’s camp, and he told us that when they heard women and children sing this Christmas carol they were greatly encouraged. In those days it was my child’s faith in God that sustained me, and although I had many questions I did not doubt his existence. It was visible in other people who had a strong faith. They sat with the dying and raised children who became motherless during this war.

(…)

We finally began hearing rumours that something was happening in the outside world. Somebody in the camp had been able to keep a radio hidden. Many Japanese guards disappeared and we were not guarded so closely any more. One day our camp commander climbed on a wooden box and announced that the war was over; that a bomb had been dropped on Japan, and that his country had capitulated. Now he was afraid for his life. We promptly started singing the Dutch national anthem and cheered and laughed and cried. The next day the camp gates were opened and we were allowed to go outside to the small town of Ambarawa to buy food. We were warned to be careful because eating too much after a period of starvation is dangerous. Some people did not listen and became very ill.

…

Anne Rietkerk Houthuyzen

Woodstock, Ontario